Ernest Hemingway said, “All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn. American writing comes from that. There was nothing before. There has been nothing as good since.”

Mark Twain died in 1910. Well, Samuel Clemens died in 1910 –– Mark Twain goes on and on. Aside from a formidable body of work that changed the shape of American literature and a reputation as a peerless raconteur, Sam Clemens left behind a 5000-page, very much on-his-own-terms autobiography written in 1906-07 in a stream-of-consciousness style with orders that it was only to be published 100 years after his death.

In it, Mark Twain's life story jumps from old age to youth to middle age recollections from paragraph to paragraph. It stops midsentence when he feels the story has petered out, or, in the middle of a story, a thread will catch his fancy and he'll be off to the races in another direction. I found the style vivid and full of an intensely individual vitality that puts the normal “this happened, then this happened then that happened” autobiography to shame. This felt real and alive as if you were in the room with him. Like any great storyteller, if they feel their attention is wandering, they know the audience will usually feel the same way (although Twain relates a pretty hilarious incident where he tells a story 5 times before the audience ‘gets it” –– he wouldn’t give up on the joke).

Samuel L. Clemens in London, England, 1873. Courtesy of the Mark Twain Papers, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Twain said of his autobiography, “This autobiography of mine differs from other autobiographies –– differs from all other autobiographies, except Benvenuto’s, perhaps. The conventional biography of all the ages is an open window, the autobiographer sits there and examines and discusses the people that go by — not all of them, but the notorious ones, the famous ones, those that wear fine uniforms, and crowns when it is not raining; and very great poets and great statesmen –– illustrious people with whom he has had the high privilege of coming in contact. He likes to toss a wave of recognition to these with his hand as they go by, and he likes to notice that the others are seeing him do this, and admiring. He likes to let on that in discussing these occasional people that wear the good clothes he is only interesting in interesting his reader, and is in a measure unconscious of himself."

“But this autobiography of mine is not that kind of an autobiography. This autobiography of mine is a mirror, and I am looking at myself in it all the time. Incidentally, I notice the people that pass along at my back –– I get glimpses of them in the mirror –– and whenever they say or do anything that can help advertise me and flatter me and raise me in my own estimation, I set these things down in my auto biography. I rejoice when a king or duke comes my way and makes himself useful to this autobiography, but they are rare customers, with wide intervals between. I can used them with good effect as lighthhouses and monuments along my way, but for real business I depend upon the common herd.”

Samuel L. Clemens at the Hannibal train station in June 1902. Courtesy of the Mark Twain Papers, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

I got the second volume, Autobiography of Mark Twain, Volume 2 this month and loved it. I wrote about the first volume, Autobiography of Mark Twain, Volume 1 HERE and was chomping at the bit to read the next installment of a ripping good story. Spinning the text out over 3 volumes is like 1001 Nights –– keep 'em coming back for more (the last volume will be out in a few years).

Susy and Samuel Clemens in costume after enacting the story of Hero and Leander, on the porch at Onteora, 1890. Courtesy of the Mark Twain Papers, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

There are many recurring threads in the work. His family plays prominently in the text with many delightful inclusions from his daughter Susy’s youthful biography of her father that's heavy with family stories but also peppered with wise observations about Twain –– she wanted her father to have a serious reputation and didn’t like it that he was known as a humorist. She died unexpectedly of spinal meningitis at age 24 in 1896 (he thought of a 17-year old Susy as a model for his widely panned “serious work”, Joan of Arc –– he loved the subject and was hurt it was not admired by his public –– a rare misjudgment of his audience).

New York Times, Dec 11, 1906

There are strong themes that received multiple visits. One is Twain’s crusade for extended copyrights for authors (they only lasted for 42 years in the USA). Twain had no love for Congress, he said, “Suppose you were an idiot and suppose you were a member of Congress. But I repeat myself.” No wonder, at one point he had to go there to plead his case on copyrights for his compatriots. Unluckily, out of 10,000 writers under copyright, only 25 had been around long enough to have the current law be a problem and Congress didn't see the necessity to change the law for so few. Still, Twain fought on. He thought it was just wrong that the author would lose rights on his books and his publisher would suddenly reap his fees as well as their own on his work. He had no love for publishers –– they had taken advantage of him many, many times.

He had a fairly dim view of much of humanity in general, "As to the human race. There are many pretty and winning things about the human race. It is perhaps the poorest of all the inventions of all the gods, but it has never suspected it once. There is nothing prettier than its naïve and complacent appreciation of itself. It comes out frankly and proclaims, without bashfulness, or any sigh of a blush, that it is the noblest work of God. It has had a billion opportunities to know better, but cannot bring itself to do it –– it is like hitting a child."

"Man is not to blame for what he is, He didn't make himself. He has no control over himself. All the control is vested in his temperament –– which he did not create –– and in the circumstances which hedge him round, from the cradle to the grave, and which he did not devise and cannot change by any act of his will, for the reason that he has no will. He is as purely a piece of automatic mechanism as a watch, and can no more dictate or influence his actions than can the watch."

There are exceptions. He was very fond of Helen Keller, and found her to be a shining example of the triumph of the human spirit, " Helen Keller is the eighth wonder of the world....Helen Keller was a lump of clay, another Adam, –– deaf, dumb, blind, inert dull, groping, almost unsentient....Helen is quite another kind of Adam, she was born with a fine mind and a bright wit, and by help of Miss Sullivan's amazing gifts as a teacher this mental endowment has been developed until the result is what we see to-day: a stone deaf, dumb, and blind girl who is equipped with a wide and various and complete university education –– a wonderful creature who sees without eyes, hears without ears and speaks with dumb lips. She stands alone in history."

Also within the book is a great bit about his penchant for white clothes –– although what he would really like to wear was surprising, "All human beings would like to dress in loose and comfortable and highly colored and showy garments, and they had their desire until a century ago, when a king, or some other influential ass, introduced sombre hues and discomfort and ugly designs into masculine clothing. The meek public surrendered to the outrage, and by consequence we are in that odious captivity to-day, and are likely to remain in it for a long time to come.... In the summer we poor creatures have a respite, and may clothe ourselves in white garments; loose, soft, and in some degree shapely; but in the winter –– the sombre winter, the depression winter, the cheerless winter, the white clothes and bright colors are especially needed to brighten our spirits and lift them up –– we all conform to the prevailing insanity and go about in dreary black, each man doing it because the others do it, and not because he wants to.... Next after fine colors, I like plain white. "

Samuel and Olivia Clemns, Dollis Hill House, 1900: "Mamma and Papa under the oaks and beeches where we always sat and had our tea." Photograph and description by Jean Clemens. Courtesy of the Mark Twain Papers, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

He goes after big words (why 'policeman' when 'cop' will do), Immaculate conception ("worn threadbare.... If there is anything more amusing that the Immaculate Conception doctrine, it is the quaint reasonings whereby ostensibly intelligent human beings persuade themselves that the impossible fact is proven."), what makes civilization ("the whole edifice rests upon the basis of enforced slavery"), thieving publishers (a particular bête noir of Twain), immortality (not interested), taxes (the British once taxed his work as "Classified Products of Gas Factories'), psychics and palm readers (they all said he was "destitute of humor) and his idea for a Human Race Club (that would examine the daily news and pass judgement on the state of humanity). There is so much more that is as true today as it was 100 years ago (especially on the topics of religion, politics and wealth). You just have to buy the book!!!

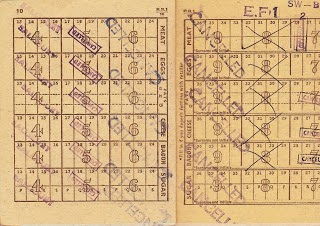

What did he eat? Although he wrote about dozens of dinners he only once mentioned food in the book, and that was a plate of Charlotte Russe being handed to him by a statuesque coed. Fortunately, I have a number of menus for Twain dinners at the Players Club (It was the Players Club menus that started Lostpastremembered just 4 years ago last month) and the Lotos Club (that I wrote about HERE and will revisit again to share a visit I made there).

Twain said, "In those days –– and perhaps still –– membership in the Lotos Club in New York carried with it the privileges of membership in the Savage, and the Savages enjoyed Lotos privileges when in New York. I was a member of the Lotos."

A much loved member if this menu is an indication, it is one of my favorite menus –– with Twain's visage sort of blooming with the rest of the flowers and the menu items written on the petals. It is kind of trippy in a good way. I had to get the wonderful archivist at the Lotos Club, Nancy Johnson, to read off the original on the dining room wall because I had a hard time making out a few of the petals. Quail aux Canapés, a grand 19th century dish, came through in the transcription. Quail or squab is on a few of the Twain menus I've seen so I think it was a favorite of his and no wonder. It is terribly good and this preparation is a knockout for any special occasion meal and fabulous with bitter greens salad to counter the richness of the little birds. I got all of my goodies from my friends at D'Artagnan, the quail, foie gras and truffle butter –– even the bacon(that I am mad about –– fabulous bacon). You could double the recipe, I know I wanted to eat them both myself. They are SOOOO good.

Quail sur Canapés for 2 (recipe inspired by Julia Child)

2 boned quail from D'Artagnan

toasted bread topped with foie gras

Sauteéd mushrooms

Bitter greens salad with Sherry vinaigrette

herbs for garnish

Put the cooked quail on the foie gras toast and plate. Add the salad to the plate with the roasted carrots and strew the mushrooms about with some fresh herbs and serve.

Sauteéd Mushrooms

1/2 lb mushrooms, sliced (any varieties will do, from buttons to morels)

1 small shallot, minced

1/2 clove garlic, minced

Sauté the mushrooms in the butter till lightly browned. Add the shallot and garlic and sauté for a few more minutes. Turn off the heat and add the madeira to deglaze the pan.

* you can use 1/2 c of demi-glace if you want the mushrooms sauced.

Toasted Bread Topped with Foie Gras

2 slices bread, crusts removed (I used a good homemade bread)

1 T butter (truffle butter is great for this)

2 oz D'Artagnan foie gras cubes and/or liver from Quail, chopped. if you have it - try to make it 1 to 2 oz. (one is pretty sparse but the livers for the little birds are small)

1/2 slice D'Artagnan bacon, chopped small and simmered in a bit of water for 5 minutes

s&p to taste

1 T cream

Butter the bread liberally on both sides and brown on both sides or toast and butter one side. Reserve

Mix the foie gras, bacon, s&p, cream and madeira until is is a creamy paste. Spread on the cooled bread. Just before serving, run it under the broiler for a few moments until bubbly.

Roasted Quail

2 boned quail from D'Artagnan

s&p

1 T minced shallots

2 large sprigs herbs (tarragon, hyssop, thyme will work well)

2 pieces bacon, sliced in half and simmered in water for 5 minutes

2 small carrots, sliced into 4 strips each and oiled

Preheat the oven and a skillet for 20 minutes to 500º.

Salt and pepper the quails inside and out. Stuff with a bit of the shallot, insert about half the butter in each one and then add the herbs and madeira. Take the pan out of the oven and lay down the carrots. Place the quail on the carrots. Cover with a bacon cross over the breast if you would like (this protects the breast meat and keeps it moist) or top with a slice of truffle butter –– that leaves bits of truffle on the top of the bird. I did it with and without bacon and liked it both ways.

Cook for 15-18 minutes and remove. Add the pan juices to the mushrooms.

2 handfuls endive, arugula or chicory -- a bitter green

1 T sherry vinegar

2 T hazelnut or olive oil

S&P

Tear the greens and toss with the oil and vinegar.

My food just wouldn't be as good without D'Artagnan and their wonderful products, thanks to Lily and Alisha and all the wonderful folks that work there.

Tis the season for giving these great madeiras to your favorite cook, I love this stuff and use them in

everything. Click HERE or ask for them at your favorite wine merchant. For something special, I love their vintage madeiras too. They are magic in food and last forever.

Thanks to Mannie Berk for sharing his amazing wines with me!

I will be taking the next 2 weeks off. I hope you all have a great holiday! I have my first article coming out next year and am playing with a book proposal so much to be done on my break!Happy Holiday and Happy New Year!

Deana (& Petunia)

.jpg)