Sir Walter Scott’s Abbotsford, Photograph by Fox Talbot, 1844

I am going to write about the man responsible for bringing the delicious romantic dream that is Scotland to the world in the 19th century–– its mythical construct rife with magic and adventure (and the inspiration and foundation for the television show, Outlander –– a seriously guilty pleasure of mine) to put me in the right mood to make fabulous Scottish game birds. What prompted my highland fling? –– it’s all about escaping the here and now.

I started thinking about it because of a piece on the news that profiled a kid who would rather play his computer games in his room 24 -7 than walk among men in the real world. He said his cyber-reality was better than the world outside his bedroom. Feckless kids who are neither smart nor agile feel empowered by their online avatar’s talent and skill (which sadly doesn’t translate to the real world as study and practice of the skills would do). It made me reflect on my own predilection for binge-watching which really does immerse you in the world of the story. After hours of watching it is an escape from reality. I wondered how easy it would be to go from bingeing to dangerous obsession (the kid didn’t eat and barely went outside). So far, my bingeing is controllable and, in a way, healthy -- I don't EVER confuse myself with Katniss Everdeen.

We all do long to escape to some degree, don’t we? I know after a grueling job, I can’t wait to ‘veg out’ for a few days on movies and binge-watch TV that I’ve missed – I love diving into other realities and escaping as a way of depressurizing. Then I am ready to go back to doing things I love to do. It’s like a vacation for my brain.

Ivanhoe (1820), set in 1194, is credited for popularizing Medievalism

Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832) by Sir William Allan, 1844

At the dawn of the 19th century, just as the world was on it’s way to changing utterly with the industrial revolution, this tradition was reborn. Men and women found the romantic world of Sir Walter Scott an irresistible escape from the tedium of their laced up lives. Scott brought the free wild world of the ancient highlands and then the epic adventures of medieval knights to the reading classes –– suddenly the rich were building new castles and even constructing their own ruins to emulate the new ideal! Scott was the first international novelist (he was a favorite of the American Southern aristocracy that helped inspired the Civil War), and pretty much invented the modern history novel -- all because he had his own reason to escape to his imagination -- polio.

Smailholm Tower

Ossian’s Dream, Ingres 1813

He studied law and became a lawyer, but his passion was the history and tales of Scotland, chivalry and romance. As he toiled at law he wrote poetry, inspired by Ossian’s poems (which were supposedly translated from original ancient texts by James Macpherson in 1760 but whose authenticity is still in doubt – at the very least Macpherson made radical changes to lesser-known ballads of the day, few of which were ever written down). The poem was full of tales of heroic lives, rich with romance – just the thing for a fertile mind like Scott’s and a great escape from his dry law books. Unlike Macpherson, Scott went to real balladeers and listened to their magical stories (using twigs to carve notes for himself so as not to offend the storytellers with scribbling them down – they were oral tales after all and the property of the storyteller).

Illustration from Waverley

I love this stuff and took a course in college called Ballads and Balladry. The professor actually played ancient recordings of Scottish balladeers telling the tales. I particularly remember one terribly old lady – her voice was like rustling paper and yet it could pull you in like a spell -- that voice could be strong and masculine or young and innocent as the tale required. The tales were sometimes spoken, sometimes sung – pure magic. I absolutely can see what pulled Scott in. I can imagine, listening in person around a camp fire with the beasties howling in the shadows, well, it would have been captivating. The talent of the storyteller would send the imagination into hyper-drive. Those tales certainly compelled Scott to put them to paper to share them with the public who could then virtually join him at those campfires (I often wonder if kids today that have had all the heavy imaginative lifting done for them are missing something –– they aren't creating scenes inside their heads as readers and listeners do). Scott’s first collection of border ballads, The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, was published in 1802. His popularity exploded soon after.

Abbotsford study Photo on Trekearth

Abbotsford hall, Photo on Trekearth

Abbotsford parlor, Photo from Trekearth

Thanks to the incredible success of his poems and novels like Waverly, Ivanhoe, Rob Roy and Heart of Midlothian, Scott could afford to build a magnificent house that was to be named Abbotsford. Great men and women from all over Europe –– artists, writers, statesmen, kings and queens, lords and ladies would come there to visit him. The Scottish Baronial style of Balmoral Castle was inspired by Abbotsford.

JMW Turner, Abbotsford 1831

JMW Turner, Abbotsford 1831

JMW Turner, Abbotsford 1831

JMW Turner, Abbotsford 1831

A Scene at Abbotsford, Landseer, 1827)

The much beloved animal painter Edwin Landseer (1802-1873) came to Abbotsford to paint Scott’s beloved deerhound, Maida (a male dog named after a famous battle), at the end of the dog's life. Landseer made many sketches and this touching painting. Scott was known for his deep attachment to his dogs (he once cancelled a dinner engagement because a dog had died).

Henry Rayburn portrait of Walter Scott

Many of his portraits and statues included a dog or two.

Statue of Maida, photograph by Fox Talbot

Fox Talbot photograph of area around Abbotsford, 1844

Gate at Abbotsford by Talbot

Early photographer Fox Talbot (who I wrote about HERE) was lured there in 1844 by Scott’s work and captured the area in remarkable photographs that were collected and issued in what was to become the first coffee-table travel book, Sun Pictures in Scotland after Scott’s death – both Turner and Talbot were seduced by the lore and the majesty of the landscape as Scott had been as a boy. I am sure Scott’s storytelling had helped both men see the beauty with an enhanced perception colored by the romance and adventure in Scott’s novels and poetry.

The room where Scott spent his last days, a dining room made into a bed chamber

Ashestiel by JMW Turner, where many of Scott’s most famous works were written

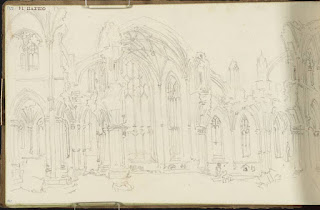

I found a story in the first of the many volume set of Scott’s Memoirs that supports my assertion about Scott’s prowess as host. It seems Scott’s friends were enchanted by a Scott-led tour of his beloved countryside. They gushed, “It would be idle to tell you how much pleasure and instruction his advice added to a tour.... On our return from the Highlands, at Ashestiel – he had made us promise to visit him, saying that the farm-house had pigeon-holes enough for such of his friends as could live, like him, on Tweed salmon and Forest mutton. …. He carried us one day to Melrose Abbey or Newark – another, to course with mountain greyhounds by Yarrow braes or St. Mary’s Loch, repeating every ballad or legendary tale connected with the scenery – and on a third, we must all go to a farmer’s kirn, or harvest-home, to dance with Border lasses on a barn floor, drink whiskey punch and enter with him into all the gossip and good fellowships of his neighbours, on a complete footing of unrestrained conviviality, equality, and mutual respect.” Scott shared the experience of his Scotland, not just a 2-dimensional postcard tour.

JMW Turner Ashtiel

And his talents for setting a table played upon his pages as well as in his dining room. A magnificent woman named Kay Shaw Nelson wrote about Scott and food in his life and novels, giving a dozen or more examples of food scenes in his books. She said of his personal eating habits, “Scott’s tastes in food were said to be plain and Scottish, and he maintained a lively interest in foods that were grown in his country, regional fare, and is known to have enjoyed the conviviality of fine dining in his home, at clubs, and while traveling. “The Wizard of the North” was familiar with the kitchens of royalty, aristocrats, and crofters.” She noted “ At Abbotsford House in the Borders where the author lived the life of a country magistrate and the landowner, his breakfast, served about nine, is said to have comprised porridge with cream, salmon, fresh or kippered, home-made ham, a pie, or a cold sheep’s head followed by oatcakes, or slices of brown bread spread thick with butter.”

N.M. Price Illustration for Guy Mannering

His novels were stuffed with scenes of dining and drinking and the bounty of Scotland’s fields and streams. That’s where I come into the story. You see, I have in my possession some real Scottish partridges and pigeons from D’Artagnan that I have been dying to make into something great

I am not new to Scottish cuisine. Probably the first cookbook I ever bought was F. Marian McNeill's Scots Kitchen: Its Traditions and Lore with Old-time Recipes when I was still in college and fresh from Ballads and Balladry -- I was thoroughly enchanted by the lore. McNeill is a fine historian and she peppers her cookbook liberally with quotes from Scott's novels and a whole slew of rare Scottish tales and bits of literature including much from Meg Dod's cookbook (that I wrote about HERE).

Meg Merrilies

Hard not to be a bit in love with Meg Merrilies, isn't it (after a walking tour in Guy Mannering country John Keats certainly was –– he wrote a gorgeous poem about her HERE)? I felt the colorful scene, spiced with a bit of larceny just begged me to use my little birds as an homage to Walter Scott, but it being summer, I was not quite in the mood for a stew (this simple game stew even crossed the channel, dressed up as Potage a la Meg Merrilies de Derncleugh!).

From Scott’s novel, Guy Mannering (1815), McNeill told the tale of Meg Merrilies gypsy stew, "It was in fact the savour of a goodly stew, composed of fowls, hares, partridges and moor-game, boiled in a large mess with potatoes, onions, and leeks, and from the size of the cauldron, appeared to be prepared for half a dozen people at least. 'So ye have naethin' a' day?' said Meg, heaving a large portion of this mess into a brown dish, and strewing it savorily with salt and pepper. 'Nothing', answered the dominie, 'scelestissima! - that is - gudewife!' Hae then', said she, placing the dish before him; 'there's what will warm your heart ....Theres been mony a moonlight watch to bring a' that trade thegither,' continues Meg; 'the folks that are to eat that dinner thought little o' your game-laws.'"

Meg Merrilies and her stew from Guy Mannering

The lovely Meg Dod cookbook, inspired by Scott himself, has some fabulous ideas for roasting native birds – traditional Scottish recipes from the 19th century. McNeill and Dod both describe cooking grouse tied with heather dipped in Scotch -- I borrowed the idea for my pigeon (I would have used heather but I had none –– I really want to try it now).

Meg Dod has a smashing gooseberry sauce to serve with them . It is a perfect counterpoint to the rich dark flesh of a bird that forages on heather and berries from Scotland’s heaths. They are spectacularly flavorful. Close your eyes and dream of the Scotland of Highlander & Rob Roy, heather scented moors and craggy ruins -- yup, I'm there.

Scotch-Scented Pigeon with Gooseberry Sauce (Serves 2)

2 Scottish Wood Pigeons from D’Artagnan

2 T Scotch (I used Lagavulin, a very peaty Islay single malt)

2 bay leaves

2 sprigs thyme

2 large D’Artagnan foie gras cubes (I love these great frozen cubes. I just chop off what I need and thaw so I always have foie gras around) or use the liver in the birds

salt and pepper

4 T butter

¼ to 1/3c gooseberry elderflower jam (you can use blueberry if you can't find gooseberry)

¼ c fresh gooseberries (optional - - can use blueberry)

2 t heather honey (optional)

1 – 2 T elderflower vinegar*

1 carrot, cut into sticks

Remove the birds from the fridge and dry them off. Pull the heart and liver out of the birds and reserve. Cover and let them warm up for about ½ an hour, then salt and pepper the exterior and interior and put a bay leaf in each bird’s cavity. Sprinkle a bit of the Scotch into each bird.

Preheat oven to 475º. Put 2 T butter in a pan and brown the pigeons (put most of your effort toward the bottom of the bird since this takes longer to cook –– gently brown the breast –– 90% of the meat is in the breast so you don't want to overcook the rich dark meat). Let them cool a bit as you lightly salt and then sauté the foie gras or bird's liver in the pan for a few moments. Put the foie gras or the bird's liver in the birds with a few gooseberries if you have them or just some of the jam. Add the thyme.

Melt the rest of the butter and add the rest of the Scotch in a small bowl. Lay the carrot sticks down and place the birds on them in the pan. Brush some of the Scotch butter on the birds and put in the oven.

Cook for 10 minutes, brushing with the butter after 5 minutes.

While the birds are cooking, put the rest of the jam, honey and the berries in a sauce pan. Add the vinegar to taste and warm. Pour in the rest of the Scotch butter and reserve.

Take the birds from the oven and let rest covered for 5-10 minutes (eat the delicious carrot sticks as you wait or serve with the birds). Serve with the sauce and don't forget to scoop the foie gras and berry stuffing out of the bird!

* just take some white wine vinegar and either add a bit of dried elderflowers (tea or loose herbs if you can find them) or some St. Germain Liqueur.