Diane de Poitiers, School of Fountainbleu, 1550-60

I was lucky enough to have a pretty decent ‘classical’ education. Still, it was a zillion years ago and since then I have reinforced some subjects and lost others somewhere down my rabbit hole of a memory. I was always pretty good with British history and most Italian but a bit dodgy on France before the 19th century.

I was daydreaming about great mistresses and courtesans after reading about Kitty Fisher last week (let's be honest, I am endlessly fascinated with courtesans and their brief flaming lives) and Diane de Poitier popped into my head as a possible subject. I realized what I knew about her was pretty slim –– 16th century France fell into my memory gap. When I finally read up on her in Princess Michael of Kent’s The Serpent and the Moon: Two Rivals for the Love of a Renaissance King I was enchanted - what a story, what a dame! Just as I was thinking, ‘wow, would this make a great film', I found I was not alone –– looks like I'm not the only person she's seduced lately. Downton Abbey's creator, Julian Fellowes, is writing a script based on the book (The Princess might have better access to Mr Fellowes than most, since his wife is her lady in waiting).

Catharine de Medici (1519-89) by Tito di Santi

Henry II of France (1519-59)

Soon to be King of France, the 18 year-old dauphin began his affair with Diane de Poitiers when she was 38 and stayed head-over-heels in love with her till he died. He called her name with his last breath (Catherine would not allow Diane to be with him at the end or let her attend the funeral -- hate triumphed at last).

The accident of Henry II

Armor of Henry II by Étienne Delaune and Jean Cousin

The shield of Henry II

Henry’s famous death (one of Nostradamos’ few correct predictions), was caused by a lance through his eye at the very last moment of a joust ––he just wouldn’t concede to another rider. He returned to the field even though his visor wasn’t fastened properly and the other rider protested his lance had been damaged -- the lance splintered and the visor broke.

Henry did live 12 days after the accident and was lucid and giving orders most of the time, even telling everyone it wasn’t his adversary’s fault it happened –– his “Hate and Wait” wife didn’t abide by this pardon and eventually captured the poor man and killed him. Henry might have lived had they cracked his skull to let the pressure out –– they were afraid of the pain it would be too much for the king. Instead of wailing helplessly in despair at the tragedy, Diane acted decisively and secured a surgeon who had successfully removed a lance to the face for another courtier so it was possible to recover from such a blow.

Diane appuyée sur un cerf by Goujon

Looks like everything I thought I knew about Diane was wrong. Diane de Poitiers was not just some lady of easy virtue. She came from one of the most respected families in France (far better lineage than Catherine Medici). She was beautiful, beautifully built and brilliant. The family motto was “Qui me alit me extinguit”—“ He who inflames me has the power to extinguish me.” She spent much time at court and was welcomed to the inner circle of the royals at the knee of Anne de Beaujeu, who was “tall and severe as a cathedral”. Anne was known for her genius at molding young girls into great young women. “Madame de Beaujeu’s extraordinary influence on her young pupils could be attributed to her example of chastity, her sense of humor, and her dedication to duty. Hers had been a varied education, and the children in her care were taught to study the philosophies and logic of Boethius and Plato as well as the writings of the fathers of the Church. Diane also learned from this wise, highborn lady the true meaning of the dignity of her rank, nobility of behavior, taste, deportment, and, above all, to despise intrigues. Anne urged her charges to bear in mind that society was still rough and vulgar and had need of their refining influence, to add their gaiety, refinement, grace, and patience to any gathering. She taught them the art of conversation, how to communicate with strangers, and not to discriminate between classes.’ She actually codified her rules and theories in a book, Les Enseignements d’Anne de France à sa fille Suzanne de Bourbon, just a quick scan shows why she was so successful, it is terribly sound advice that comes from the best of the tradition of courtly love – a tradition Diane and even Henry II believed in:

“Always dress well, be cool and poised, with modest eyes, softly-spoken, always constant and steadfast, and observe unyielding good sense.…God, who is justice itself, may tarry, but will leave nothing unpunished. Nobles are the kinds of people who must see their reputation go from good to better, as much in virtue as in knowledge, so that they will be known …,” and “Another philosopher says that gentility of lineage without the nobility of courage should be compared with the dry tree which has no leaves, no fruit, and which does not burn well.” The simplest of all her advice was: “Avoid sin.”

“The book’s final instruction, said to come directly from Louis XI, is: “En toute chose on doit tenir le moyen”—“ Always keep a balanced view of everything”— a maxim Diane tried never to forget.”

Francis I (1494-1547) by Jean Clouet, 1530

The court of Henry II’s father was fun, energetic and full of brilliant men. After all, it was Francis I who brought da Vinci to France to Château du Clos Lucé and encouraged humanism to thrive. He thought da Vinci was a national treasure and left him to paint and invent.

da Vinci drawing of lion

When da Vinci died, Francis bought the Mona Lisa from his heirs (da Vinci traveled to France in 1516 to be "First painter, architect and mechanic of the King" designing projects, buildings and even festival treats like the mechanical lion in 1517). Leonardo died at Château du Clos Lucé in 1519. Francis said of Leonardo, “For each of us, the death of this man is a bereavement, since it is impossible that we will ever see his like again.”

Cellini’s priceless golden salt cellar created for Francis I

Another of the grand artists who spent time with Francis was Benvenuto Cellini. He very much enjoyed his time at the king’s new Fountainbleu (named after a favored dog name Bleu who was lost and then found in a clearing in the woods by a spring). Cellini called the château “Fontana Belio.” His sketches and wax models always delighted the king....” When the cellar was stolen in 2003, it was valued at $48 million dollars (it was recovered a few years later).

“François I was one of the most attractive and exciting personalities ever to sit on the throne of France— tall, dark, well built, he was thought most handsome (despite rather spindly legs), and very regal. He also had great charm and blind courage, and neither he nor anyone at his court believed there was a woman living who could resist him. He saw the court as a font of pleasure, his own and that of his courtiers. This was an era when tales of chivalry exerted a powerful influence on the young courtiers around the new king”. Francois I court was a great place for women for he felt, “A court without ladies ’tis like a year without springtime, and a springtime without roses.” Brantôme writes: “Although he held the opinion that they [women] were highly inconstant and variable, he would never hear anything said against them in his Court and required that they should be shown every honor and respect.”

Anet

King Francis visited Diane at her beautiful Anet and loved the society there. “It was during this stay at Anet that the king decided to form his band of twenty-seven maids of honor, “La Petite Bande.” Chosen for their looks and intelligence, these young beauties were to accompany his court wherever it went, and he invited the glorious châtelaine of Anet to be one of their number.”. Diane was one of these ladies and “Belle à voir, honnête à hanter”—“ Pleasing to look at, honest to know.”

Princess Michael tried to paint a full picture of life at the time and so, luckily for us, described food at Francis table. “Meals at court were served on tables piled high with assortments of food; plates and scented napkins were discarded after each course. Everyone in France ate with just a knife, a spoon, and their fingers; no fork as yet. Napkins were always placed around the neck because eating with one’s fingers was never tidy. Ladies would sometimes place a small piece of meat on a slice of bread to make it easier to eat. Pâtés were popular and often spread on bread. Different sorts of meat and game were always part of a court buffet, as were sweetbreads, dressed crab, quenelles, and truffles, which were very popular. The sideboards groaned under the weight of assorted vegetables, wild mushrooms, even codfish. For dessert there were endless sweetmeats, fresh and jellied fruits, some in pastry, and many kinds of mousse. In the main, the food was heavy and rather indigestible. Wines, often spiced, flowed in great quantity and helped to loosen tongues.”

Francis modeled the lifestyle at Fountainbleu after the ideas found in The Courtier. “François loved to talk— conversation was one of his greatest joys, and there was no greater book for teaching the art of conversation than The Courtier. Castiglione wrote that “all inspiration must come from women.…Without women nothing is possible, either in military courage, or art, or poetry, or music, or philosophy, or even religion. God is truly seen only through them.”

Tragically for her, Henry was not much inspired by his wife. Catherine was not terribly attractive or charming. No wonder, she was used as a pawn by her family as much as Henry had been –– in a way, their backgrounds were not dissimilar. Henry and his brother were used as collateral in an exchange for his life after Henry was captured. They remained imprisoned in Spain with varying degrees of comfort but mostly in the dark and alone. It was a horrible way to spend their childhood. It is doubtful Henry ever forgave his father.

Diane de Poitiers

When he was handed over as a hostage, the last loving embrace he was to know came from his mother's lady in waiting –– Diane de Poitiers took pity on the poor child and held him close. He never forgot the kindness. She was there when he returned from his ordeal as well and eased his discomfort. She helped him become the man he was. Under her love and expert guidance, he went from a sullen, lonely boy to a fine man. “HENRI the king was very unlike Henri the prince. The change was remarkable. He became more affable, more open and friendly to all comers; he smiled often and laughed. His coronation had a mystical effect on him as well, and he carried himself with a new dignity and pride. Naturally affectionate, he was sentimental, honest in word and deed, and faithful to his friends. He was a contemplative man, who loved to read; he was steady, moderate, profound, and rather silent, yet the members of the court recognized his goodness of heart. Henri was a romantic knight from the days of chivalry, quietly going about his business and focusing on his goal with a steadfastness akin to obsession. That obsession was Diane and her glory, just as hers was his. Henri wished to demonstrate his love for his mistress in every possible way.”

She used her intelligence as well as her feminine wiles. Diane de Poitiers was nearly 50 and the 28 year old King of France was madly in love with her.

Diane de Poitiers, Fountainbleu School

Princess Michael even discovered some of her beauty formulas, “… a powder made of musk and rosewater and a paste used against wrinkles that she mixed herself, from the juice of a melon, crushed young barley, and an egg yolk mixed with ambergris. She applied the paste to her face like a mask. Whenever Diane was alone, she slept propped upright on deep pillows to avoid creasing her face.” Aside from the ambergris and musk, these preparations wouldn’t be considered strange on today’s dressing tables.

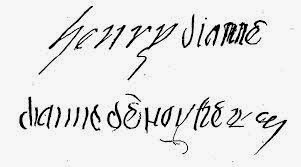

The bed Henry and Diane shared at Anet (not the black and white paneling with Henry’s initial)

“When Diane was forty-eight, Henri begged her to accept and wear a ring “for love of me. May it always remind you of one who has never loved and never will love another but thee.”

He also wrote her this:

Once more a prince (oh, my only princess!)

My love for you will never cease

Resisting time and death

My faith has no need of a fortress,

A deep moat or fortified tower,

For you are my lady, queen and mistress

For whom my love will be eternal!

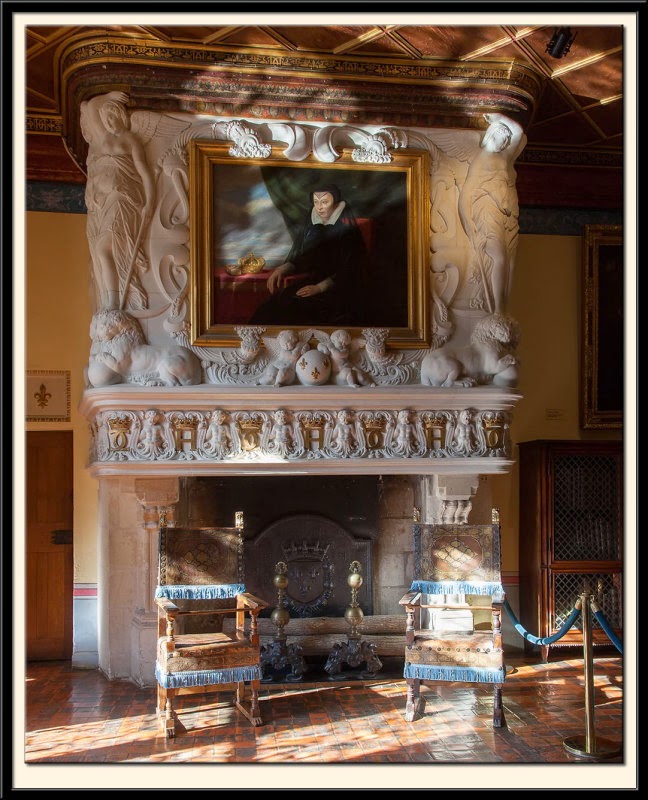

Goujon Fireplace in the bedroom at Chenonceau (Chris Brooker photo)

Chateau Chenonceau bedroom (photo from Phareouest)

Diane and Henry spent nearly all their time together, traveled from house to house but were happiest at Anet and Château Chenonceau (a house that Catherine had long coveted and that she took back from Diane the minute Henry died).

Lucky for us, food is not forgotton in the narrative of the book (you must be hungry by now!). To set the scene, Princess Michael explains, “The mid-sixteenth century was also the time when French gourmet food emerged. French cuisine began to achieve such a reputation that foreign princes sent to France for chefs and pastry cooks. The expression “faire bon chère” litters the correspondence of the time and was used to signify the quality of the guests’ welcome and comfort as much as the excellence of the fare. “

“Cookbooks had been available since the advent of printing and the cult of cuisine was developing. Already some members of the court were known for their appreciation and knowledge of good food, among them Henri’s friend Jacques de Saint-André, who wrote of the splendor of the food to be had at Anet and Chenonceau.”

“At her own table, Diane preferred to drink vin claret or rosé. Her wines came from her vineyards at Chenonceau or from Beaune. Although dairy products were considered more suited for the use of the common people, Diane believed in healthy food and served butter and cheese from Normandy at her table. Traditionally, there were three courses for dinner or supper— boiled food, followed by the roasts, and then fruit— a departure from earlier in the century, when dishes were brought in one after the other with no heed for order. Fish, including whale and dolphin, came from Rouen and was often cooked in white wine. It was used especially on Fridays and on “days of obligation” (religious fast days). According to Erasmus, during Lent, the kitchen was busier than ever as the chefs were hard put to render delectable the meager rations permitted. Diane’s table was always laden with an abundance of food. Pork was butchered into ribs or chops, or was sometimes served as hams or sausages made from the trotters or the ears. Beef, lamb (the tongue was a delicacy), and poultry were in abundant supply. Vegetables— especially cabbage, spinach, leeks, and turnips— were cooked in lots of water (probably boiled tasteless) and often pureed to digest more easily. Cooked together with the meat, the vegetables ended up as a sort of stew, which was easy to eat with a spoon. There were still no forks. All this fare was accompanied by a variety of sauces, hashed meat, and pastries. Wine was drunk warm (blood temperature), but slowly the fashion for chilling white wine came from Italy. White wine was then drunk at cellar temperature or snow and ice added. The Italian [actually French Huguenot] sculptor Bernard Palissy designed a clay drinking fountain for keeping wine chilled in the summer months” (do look at Palissy’s extraordinary work that prefigures art nouveau by centuries – wild magical stuff. He was conferred the title of "the king's inventor of rustic figurines" by Catharine de Medici and was a personal favorite. She even protected the Protestant Palissy from prison and death).

late 16th century French fork and knife

16th Century royal napkin from England

18th century copy of Bernard Palissy plate with Henry's initials (with a C for Catharine)

To give you a sense of Diane’s table, a recipe from one of the great medieval cookbooks by Chiquart, written in France at the beginning of the 15th century. It details a menu for a grand dinner (considering Francis had 18,000 in his retinue it would have been a Herculean task to feed them normally, let alone on a special occasion), and then gives nearly 100 recipes for dishes served (although many are very similar to one another with only minor changes).

Chiquart writes in his book, Du Fait de Cuisine

“In the year of grace 1400 Aymé, first duke of Savoy, my most dread lord, received as a guest my lord of Burgundy and for this I, Chyquart, who was his cook in those times, in the course of my duty made, prepared, and ordered to be prepared many notable dishes for the dinners and suppers of this feast; and so ordered, made, or had made by the command of my said and most dread lord at the first course of the dinner of the first day, while ordering to be written down the things which follow…”

It does seem like there was a certain ying and yang to meat and fish dishes with one offsetting the other on the banquet table. I was curious when I read the recipe for a sauce that had a bean base. I had to try it. Although it was used on fried fish, I thought it would be great with chicken… especially if wood grilled. The smoky flavor complements the sauce. What you have in the end is an interesting proto-pesto that is quite rich and creamy but low fat and high flavor.

Du Fait de Cuisine 1400

26. And to make pottage opposite the bruet of Savoy made above for a meat service: to make another of fish opposite that one, take your white bread and cut off the crust very well and take it according to the quantity of potage which you should make, and then put it to soak in the purée of peas and white wine and verjuice according to the quantity which you are making of the said potage. And arrange that you have a great deal of parsley, and sage, hyssop, and marjoram; and have a great quantity of the said parsley picked over, and put in the other three in moderation because they are strong; and put together, then wash them in three or four changes of water well and properly, and take and press them between your hands and drain off the water and wring them and put in a mortar and bray well and properly; and when they are very well brayed put them with your bread. And take your spices, ginger, grains of paradise and a little pepper--and not too much--and strain it very well into a fair cornue; and then put them to boil in a large, fair and clean pot according to the quantity which you have, and let it just come to a boil so that the color of the greens is not lost; and to make it nicely put in a little bit of saffron to make it bright green. And when it is brought to the sideboard take your fried fish and put on your serving dishes, and then put the said potage on top, and scatter pomegranate seeds on top.

Herb Potage from Du Fait de Cuisine

¼ c blanched almonds, roughly chopped

½ c torn bread without crust, lightly packed

1 c cooked white beans

¼ c w wine

¼ c verjuice

1 T sugar or to taste

salt to taste

½ to 1 t ginger

½ to 1 t grains of paradise

½ t pepper

½ c roughly chopped parsley

1 T each chopped fresh marjoram, sage and hyssop (use thyme if you can’t find hyssop)

½ t saffron in 1 T hot water

pomegranate seeds

Put the almonds in a blender or processor. Grind. Then add the bread and beans and the wine and verjuice. Add enough water to make a good paste. Next add the sugar, salt spices and herbs and saffron and blend.

Put into a saucepan and warm gently (it must be heated or the spices taste raw and bitter). Add enough water to make a sauce consistency. Check for flavor (you may want to add verjuice or spice as the beans seem to mute the flavors). The original recipe does admonish that you shouldn’t go overboard with spice or the stronger herbs so don’t lose the spices in the sauce but you can put in a bit more than you might think.

Sprinkle with pomegranate seeds and serve.

%2C%2BQueen%2Bof%2BFrance%2B(1547-59)%2Bby%2BTito%2Bdi%2BSanti.jpg)

.jpg)